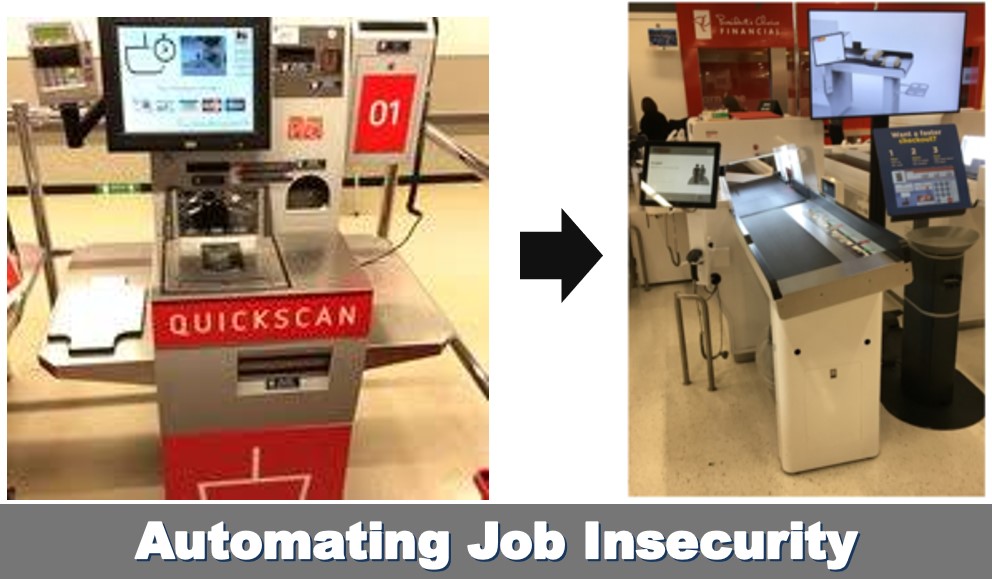

A real estate agent and a pharmacist are standing in the “12 items or less” line at a supermarket. Next to them, where the other express line used to be,there is now a large scanning machine, resembling the ones you send your carry-on luggage, shoes, and laptops through: a conveyor belt on the bottom, and a tunnel though which all items must pass before emerging on the other side.

This supermarket scanner does not use x-rays. It uses lasers, weigh scales, and photo-recognition technology to identify every item placed on its belt, thus removing the need to scan bar codes, and theoretically speeding up the checkout process.

The estate agent and the pharmacist regard this new machine with scorn, sharing a few words about how it will merely take away a few more jobs. The supermarket employee who oversees the machine, helping customers with their questions, and occasionally unjamming the conveyor, smiles to herself as she hears this.

Working, as she does for the supermarket, she has seen three cashiers including herself, upgrade their skills from shifting groceries from cart to bag to overseeing the machine’s every working moment. She is taking micro-courses in coding and diagnostics to work as the conveyor’s mechanic.

She looks at the two professionals, whose careers in real estate and retail pharmaceutical stand directly in the firing line, as disruption and displacement bear down on them.

It is often thought that new technologies, especially those using the cloud, the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, and machine learning will pose a substantial threat to a specific group of jobs, most specifically lower-skilled, labor-intensive positions, whose activities can be done more quickly and accurately using robots and computers.

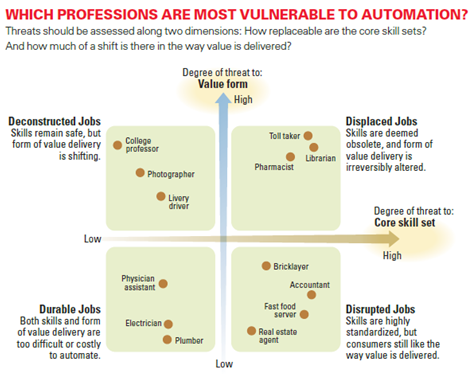

But this is not the case. The threats and opportunities posed by advancing technologies apply to a much wider spectrum of the workforce, as the authors of a recent MIT Sloan Management Review article point out. The authors observed the type of value jobholders delivered to end customers (either retail or internal) and the skills they used to deliver it and identified four paths of evolution for jobs: disruption, displacement,deconstruction, and durability.

Certain skilled manual professions, like plumbing and electrical work seem largely immune to intelligent technological change, since the value of the work is based both in motor skills, abstract thinking (problem assessment and solving) and a good amount of experience. These are classified as durable. Real estate agents and pharmacists will not be so lucky. Their professions, along with librarians and software developers, are seeing much of their current responsibilities being moved into the same bracket as telephone operators and toll takers. They have become displaced, requiring modifications and upgrades to their skill sets.

Figure 2 Johari window of job vulnerability, published in the MIT-Sloan Management Review article.

The cashier in the supermarket who now oversees the scanner is an example of someone whose first job was a victim of disruption, in that the value form requested by the customer (cashing out the groceries) still exists but has been disrupted by technology. But she can also be seen assn example of deconstruction, in which “the core skill set remains safe, but the value form is threatened.” This means that her position now is to still assist shoppers in paying for their groceries, but the way she does so, working alongside the scanner, represents a deconstruction of the activities that support the same service.

The authors of the study point out that not only are all jobs destined to be placed in one of these four quadrants (disruption, displacement, deconstruction, and durability), but the type of education and retraining needed to move through any one of these four (including durability) is also changing.

“[Workers] should focus on quickly acquiring the most relevant skills in an area with a relatively stable value form. In a volatile job market, length y programs that require years to complete (such as extra bachelor’s degrees) are likely not the best approach. Micro-credentialing programs — competency-based certifications, mini-degrees, and digital badges — deliver qualifications more quickly and offer more options on the path to a degree along with a sense of accomplishments individuals obtain marketable skills fast.”

Resistance to Change as a Career Threat

The authors also point out how much of the danger to an individual’s long-term career prospects has its roots in simple change resistance. Many will turn their backs on change and the opportunities it brings out of fear and resentment. This is a very human reaction but one whose days must be limited out of necessity. Stubbornly holding on to the past tends to alienate the professional even further from employment opportunities, as can be seen in the vocal and counter productive reactions displayed the world over by professional cab drivers, who took to the streets and slowed traffic in urban centers all over the world to protest the existence of decentralized ride sharing programs like Uber and Lyft.

The authors leave us with a final message that suggests that “understanding core skills and value form as the key units of analysis will help job holders of all types respond to workforce changes.” Yet I remain curious as to whether, in writing this article, they used an online grammar and readability app to ensure their prose was even better than their respective levels of experience would allow. This is not a criticism, simply a topical observation.